Jan Boelen. Designing a New Industrial Revolution

In an essay for exhibition The Machine – Designing a New Industrial Revolution, Jan Boelen reflects on changing production methods from Industrial Revolution to DIY 2.0 and from rise of network culture to the Slow Movement.

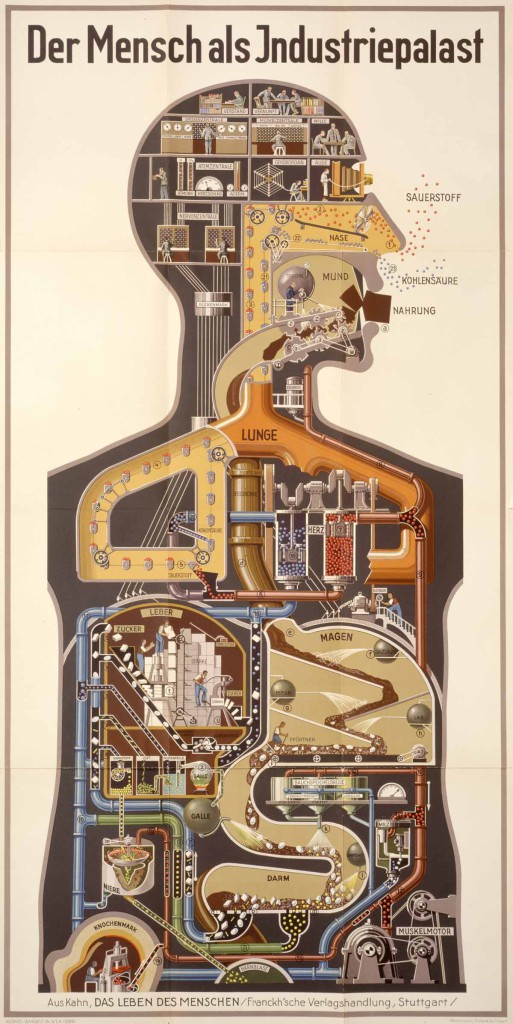

Der Mensch als Industriepalast. Man as Industrial Palace. In 1927 Fritz Kahn made an illustration of a human being as a factory, where every organ is replaced by a machine, operated by little people. Kahn demonstrates a crossover between industrialization and science, an analogy between human physiology and the operation of contemporary technology.

The human as a factory, this seems to be true now more than ever. Not only is the body a machine, able to produce many materials – designer Thomas Vailly uses his own hair to make little cups – but people can also produce anything anywhere. A new industrial revolution is taking place, suggests Design Hub Limburg.

This summer, Z33’s exhibition ‘The Machine’ will be presented in C-Mine, Genk. On the ruins of a former coalmine area, between old machines reminiscent of the industrial revolution, Design Hub Limburg demonstrates a new industrial revolution, not in factories, but at home.

A little history

The First Industrial Revolution began in the United Kingdom in the late 18th century, with the mechanization of the textile industry. Tasks previously done by hand in hundreds of weavers’ cottages were brought together in a single cotton mill. The factory was born. The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, came about in the mid 19th century after the invention of the steam engine, the internal combustion engine, electricity and the construction of canals, railways and electric power lines. Henry Ford’s invention of the moving assembly line, making mass production possible, gave this phase a boost.

In recent years there is talk of a Third Industrial Revolution, where manufacturing goes digital. If the First Industrial Revolution was one for engineers, then now designers are at the forefront of a new revolution. They are part of networks that enable them to develop new materials, build their own machines and systems, and look for new tools for production and distribution. These developments offer an alternative to mass production, and open paths to a new economy and society. Man as Industrial Palace, yes, but even more so: man as a mini-factory for home fabrication.

You say you want a revolution

Technological revolutions have often engined social change. Most influential were the liberating effects of the technologies of decentralization, writes Tal Erez in his thesis for Design Academy Eindhoven, ‘Socialism: looking forward. Design for a new consumer’. Be it of knowledge (the printing press), of consumption (the industrial revolution) or of information (the internet). Now, the 3D printer and the use of open-source for objects enable the decentralization of the means of production and the production processes themselves. A hierarchal, vertical, centralized, top down and copyrighted system with passive end users and static products makes way for a network based, horizontal, decentralized, bottom up, partly copyrighted system with active end-users and dynamic products.

People have been longing for an alternative to mass production since its debut. The Do-It-Yourself movement has its roots in the fifties, as a re-introduction of the old pattern of personal involvement and use of skills in upkeep of a house or apartment. Two decades later DIY came to be associated with the punk and skate subculture where musicians and skaters made their own music, record labels, skate videos and magazines. American punk rock band Black Flag was regarded as a pioneer in the movement of underground do-it-yourself record labels. In this context, DIY is related to the Arts and Crafts movement, which was a reaction against the impoverished state of the decorative arts and the conditions in which they were produced in the 19th century.

Today as well, people keep making things themselves: they grow kitchen gardens instead of buying their vegetables at supermarkets, they sew their own clothes instead of shopping at big chains. But this new revolution is much larger than that. DIY 2.0 has arrived.

DIY 2.0

The digital camera and Instagram transformed everyone into a photographer. Now developments like Open Source and 3D printing can make a designer or a producer out of everyone. Eugenia Morpurgo developed Repair It Yourself Shoes, a pair of shoes with a DIY kit to repair and customize your own shoes. Shoes are an emblematic product, because with the rise of consumerism and mass production, they evolved drastically away from a completely repairable object. And the active social-economical structure that existed around shoe repair is slowly disappearing since mass produced shoes are not meant to last longer than a year, they are designed to be tossed out after a year, so that the consumer can buy new pairs every now and again. The activity of repairing is a form of re-appropriating control on our material world, so this project brings back in the hand of the consumers tools and knowledge for repairing.

RIY shoes engage with the consumer online, becoming themselves a platform to generate and exchange skills on repairing. The platform is related to websites like Instructables, E-how and Youtube, where users create an immense database of techniques and projects stimulating the creativity of other users. In the context of the exhibition ‘The Machine’, the Repair It Yourself project take the shape of an interactive installation that generates and shares repairing skills.

Another example of DIY 2.0 is the RepRap (Reproducing Rapid prototyper) 3D printer. The device is completely open source and costs about 500$. It is able to print digital design files in 3D, and can already print more than forty percent of the parts of its own structure. In the years to come it will be one hundred percent self-reproductive. So the next step is the de-centralization of the designing process itself.

The OpenStructures project that Z33 instigated does exactly that: de-centralize the designing process itself. The project explores the possibility of a modular construction model where everyone designs for everyone on the basis of one shared geometrical grid, designed by Thomas Lommée and engineers of the University of Brussels. Like an advanced Meccano, OpenStructures is a dynamic puzzle to which everybody can contribute parts and objects. In this system a car does not have to be a car forever. Every object constructed with this grid consists of parts that can be used to create a new object. This creates a dialogue between user and producer, introducing a new kind of economy, which is based on collaboration and consultation.

Individuals in a network

The evolution from craftsmanship to factories enlarged the distance between producer and consumer. In their text ‘The New System’, Gardar Eyjófsson and Thomas Vailly express their hope that in a new system the alienation of the user with the object will be eliminated, thus bringing people back to the forefront of creation. “The new system brings the user to all sides of the process, meaning not just the use of the object but also its creation.” Projects like the RepRap 3D printer or OpenStructures allow users to do exactly that. Furthermore, in the new system, matter is seen as an endless flow and objects are ephemeral, like Thomas Lommée suggests.

In order for this endless flow to exist, networks are needed. Next to Eyjófsson’s and Vailly’s new system, Tal Erez proposes a new consumer, one that understands the joint power of a community, using new social networks. Because together we know more. This new consumer is taking control rather than letting himself being led by the head of a hierarchal structure. The consumer becomes someone to work with. He is a socialist with capitalist tools.

Networks are the result of many individuals together. Thanks to our connection to a network we can act alone again and make our products visible and understandable through these networks. Social networks open new possibilities for individuals. The universal grid of Thomas Lommee’s OpenStructures for example allows every individual to create their own object. If before the new industrial revolution designing and producing was the prerogative of certain people, then now everyone can do it themselves. Everyone can contribute and design an object. One individual can cause a revolution, correspondent to the Butterfly effect: a small change can cause large differences in a later stage.

From slow coffee to slow tech

Nespresso. What else? Baristas everywhere around the world know what else. Instead of using an espresso machine, the new trend is to make slow coffee, using filters. Nowadays many coffee bar owners are roasting their own coffee beans.

The decentralization of the means of production is sometimes called a revolution of home fabrication. This revolution takes place everywhere, from coffee bars to your home. Studio Formafantasma proves that it is possible to make a new kind of plastic in your own kitchen. In their latest project, Botanica, Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin create their own personal interpretation of polymeric materials, using plants to make plastic biodegradable. The organic details and plant-like forms of the pieces underline the vegetal and animal origins of the resins.

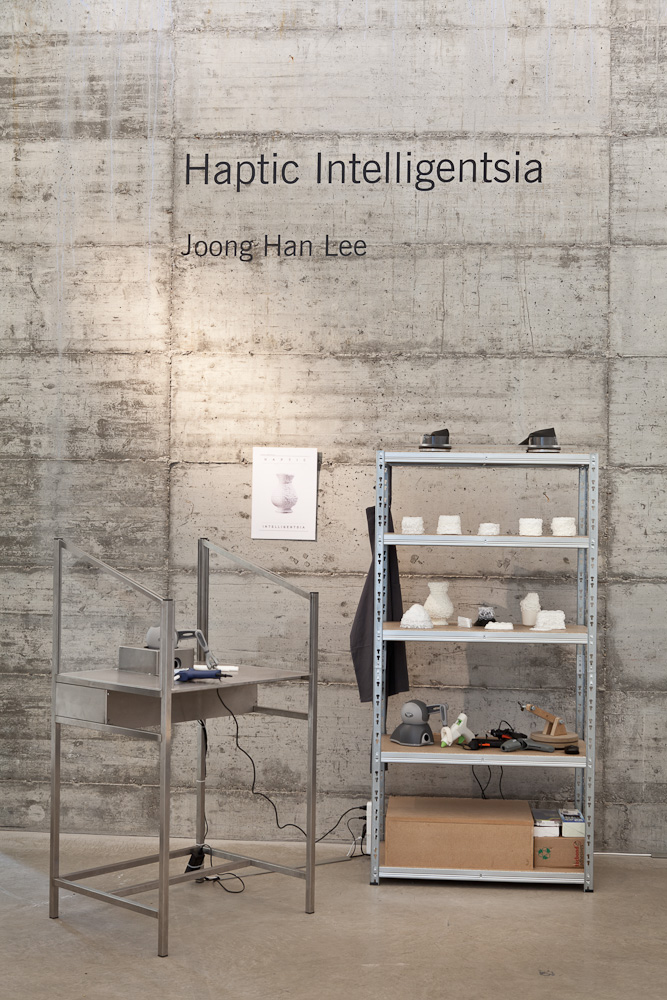

Like we said in the paragraph about DIY 2.0 handcrafted products are a reaction against mass-production. In his article ‘Make It New’ in Frame, Jeroen Junte asks: “Why not make machines that combine the age-old, unique quality of a handmade object with the efficiency of serial production?” The best of both worlds. Before the invention of printing, every object was unique and therefore irreplaceable. But this is the era of cloning: digital objects are interchangeable and the supply is infinite. The 3D printer allow objects to become unique again, but at the same time to be reproduced easily, says Sybrand Zijlstra in his article ‘De toekomst is digitaal’. Joong Han Lee, for example, implements craftsmanship in high tech in his ‘Haptic Intelligentsia’. “I put human touch in digital technology”, he says. “I embrace the poetic imperfection.” Han Lee makes clear that in 3D printing there is room for the personality of the individual. Even if the basic model is the same, every object is different and unique thanks to the individual maker.

Junte’s answer to the search for new production systems is ‘slow tech’. Small-scale serial production is no longer a fantasy. Craftsmanship meets cutting-edge technology as the use of sustainable and local resources become the norm, and 3D printers materialize the digital revolution. Production is no longer reserved for skilled workers or shrewd corporations but is completely democratized, says Junte. New relations and a new ecology emerge, which is absolutely necessary since the world’s natural resources are under pressure.

Jan Boelen is the artistic director of Z33 – House for contemporary art in Hasselt, Belgium, artistic director of Atelier LUMA Arles in Arles, France, and head of the Masters Department Social Design at the Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. He is chairman of the Committee on architecture and design of the Flemish community. In his work as a curator, Jan Boelen has worked together with Raf Simons, Studio Makkink & Bey, John Körmeling, Thomas Lommée, Martí Guixé, Aldo Bakker, Dunne & Raby, Konstantin Grcic, Joseph Grima, etc. To the initiative of Z33 and the province of Limburg, Manifesta 9 took place in Belgium in 2012. In 2014, he has been curator for the design Biennial of Ljubljana in Slovenia and he has led a series of international debates on the future of design.

Towards a new uomo universale

Man as Industrial Palace can be seen as a deterministic body: when a lung does not function properly anymore, it is simply replaced by a new one. In modernist thinking every body part was functioning in its own right, but now everything and everyone is intertwined. The human is no longer a collection of parts, but a whole. Furthermore, he is connected to other humans in networks. Maybe this third industrial revolution will create a new kind of homo universalis as well.

In the future, the body of this homo universalis will be a factory like the Industriepalast, since it is becoming a vessel of information, energy and material, a place for production and distribution. Many designers are exploring this idea. Thomas Vailly uses his own hair to develop a new kind of bioplastic, Revital Cohen developed the fictional project ‘Electrocyte Appendix’ where an individual can generate electricity with his body, and in Tuur Van Balen‘s ‘Synthetic Immune System’ some yeast and your own blood are used to create a personalized medicine.

After the home factory, we get the rise of the ‘body factory’. The factory was replaced by the home and now this home is replaced by the body. Since everyone has a body, everyone has the opportunity to be a designer. And since you carry your body with you everywhere you go, you can design anything anytime anywhere.

This body factory comes with a shift of power. Factory owners, and those in possession of infrastructure, machinery and real estate are no longer in control, writes Tal Erez in his Manifesto. The consumer and the designer, being directly linked to the consumer, now sit at the top of the pyramid. Once again resources, authorship, manufacturing and distribution are managed by designers and consumers.

This vision of the future is not at all far fetched. Already people are creating things everywhere. Just look at coffee bars you pass in the city: people are working on their laptops and creating a wide variety of things. The future is now. And the new homo universalis is a designer.

The essay was originally published in an exhibition catalogue for exhibition ‘The Machine – Designing a New Industrial Revolution,’ curated by Jan Boelen.

Footnotes

Erez, Tal, ‘Socialism: looking forward. Design for a new consumer’, Design Academy Eindhoven, 2010.

Eyjófsson, Gardar and Thomas Vailly, ‘The New System’, in ‘Trust Design. Part Three (of four) Faith is Trust’.

Junte, Jeroen, ‘Make It New’, in ‘Frame’ Issue 86.

Zijlstra, Sybrand, ‘De toekomst is digitaal’, in ‘Morf. Tijdschrift voor vormgeving’ issue 15, 2011.

‘The Third Industrial Revolution’, The Economist, April 21st 2012.