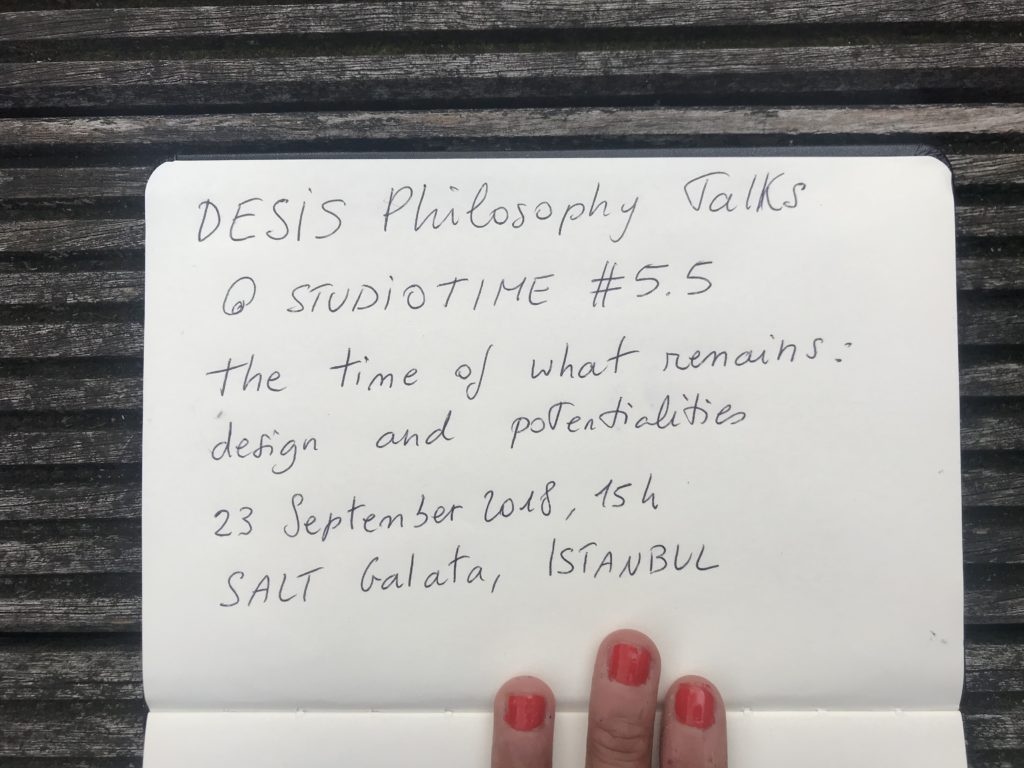

The Time of What Remains: Design and Potentialities

Each DESIS Philosophy Talk aims to explore how philosophical reflections can not only help understand but also empower new forms of experimentations within cutting-edge design research. The conversation always take place within a specific context which in this case is the exhibition Time School, one of the subthemes developed within the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial. This talk is a further expansion of the topics that were addressed at the Desis Philosophy Talk #5.4 held previously this year, at the Time School’s first presentation during the Milan Design Week.[1]

In the context of the Time School this philosophy talk links to an existing body of philosophies on time, and in particular is interested in exploring further one of the main threads developed within the Time School, the re-thinking of time as linear, mechanical and progressive towards a non-linear understanding. Here time is seen as a vitalistic force, where it is not continuation but rather the moments of breaks and rupture, that form the center of our understanding and appreciation of time.

“A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”[2]

In the linear perspective, time is perceived as a line that connects the past towards the future, and the future is a natural prolongation of the way in which we currently interpret the past and the present, and its fulfillment. This linear view of time contributed to feed the ideology of progress, according to which, as Hegel puts it, there is a logical and teleological course of history, and historical development will necessarily lead towards a better future, or in other words to progress. This we could say is also the main interpretation of time in modernist discourse.

Here, we would like to focus on Walter Benjamin’s critique on the idea of linear time, and would like to investigate which possibilities for design education and design practice this might offer. According to Benjamin we can no longer count on tradition – i.e. the traditional, progress-oriented, instrumental way to read the past – to support our way to live in the present and relate to the future. In other words, we lost faith in progress. To describe this process, a good friend of Benjamin, Hannah Arendt uses an aphorism of Renè Char: “Notre héritage n’est précédé d’aucun testament”.[3] We can no longer count on the intellectual heritage of our predecessors. Therefore, we are disoriented, and feel stuck between past and future, living, so to say, in a “gap”: attracted towards the future, and yet not being able to make sense of the past and to build on top of it [4]. All we see, are ruins.

And, yet, these ruins or what Benjamin refers to as the remains can withhold potentialities. In his aforementioned description of the Angelus Novus, Benjamin beautifully describes this unrestrainable run towards the future by using the image of a storm. It is violent, and humans seem unable to escape it. History, seen as a line promises a future that is an improvement of the present. Yet, contemporaneity, as it was also the case in Benjamin’s time, shows otherwise. Criticism towards the idea of progress and linear time not only comes from above, from intellectual theory but from the mess of the real world. In the time of remains, reality itself generates a moment of criticism. And it are precisely these moments of crisis that give people the possibility to become aware of the potentiality of what has passed unseen within the logic of progress.

When we are facing “dark times”, many of the understandings of reality we provided in the past are showing to be insufficient. In this sense, we can say that society is currently experiencing a proving-wrong of many of the key mainstream narratives which have been formatted by modernist western thinking. Benjamin says that in the “Jetztzeit”[5](the “time of the now”), the moment of the break of history, one can finally have access to what was a potentiality in the past and has passed unseen. In the remains of the failure of the ideology of progress, in what has lost its value from an instrumental point of view – and has therefore become a “fetish”[6] –lies a possibility, which can be discerned by those who are able to listen.

In his short essay on Leskov, Benjamin tells us that this should be the main feature of a real storyteller: being able to listen to the stories of the margins: in other words, to that which remains. The storyteller is he who pays “attention”[7] – the natural prayer of the soul, as Malebranche puts it – to the remains, and is able to tell its past potential and to bring it in relationship with the present and the future. The time of the break in history, is the anticipation of the messianic state, where past, present and future will be fully manifested in their interrelationship, as all being different facets of the same image, and all that has passed unnoticed, all the potentialities of the past, will be made actual.

Storytellers anticipate this time of justice, where all that has passed unsaid and all who have passed unseen, will finally be acknowledged. For Benjamin there is certainly the necessity to testify for the victims of history, but also the necessity to acknowledge a possibility of action for intellectuals, to react in the time of breaks, in the gaps, as Hannah Arendt puts it, where “new beginnings” can come into being.[8]

If we agree that, like Benjamin, who was living in the postwar period of the 1920s and 30s, we are living today in ‘a time of remains’, lacking trust in the future, and having lost the stability of the past perhaps this means we should follow Benjamin’s suggestions, and look or ‘listen’ for potentialities within those remains.

Designers are naturally projected (design as “project”) towards the creation of new beginnings. More than ever, our current dark times ask for this capacity to look at possible futures with different eyes, and consider different ideas of temporality, a perspective that is not based on the continuation of the present, which at this moment is leading us either to a global catastrophe, or to a standstill – overwhelmed by the ruins to the effect that we feel it has become meaningless to act; which of course will just as much lead us to catastrophe.

While cutting-edge designers already often implicitly deal with alternative ideas of temporality as for example in speculative design [9] or critical design and all its further diversions, this is not at all yet the case in design education. If we look at the latter – which is at the center of the Istanbul Design Biennale’s main theme, A School of Schools – many steps still need to be undertaken to move beyond a pedagogy of progress and linear time and ‘learn’ design students to think differently, and to learn how they can use the ruins of the present as a stepping stone to break away from its continuation.

Although we do not have the answers yet and it will require further research, it is clear that design education – and in extensu education in general – could learn a lot from Walter Benjamin’s ideas in terms of developing a different pedagogical approach towards time. Following in Benjamin’s footpath, Hannah Arendt says that when linear time is broken, there is unexpectedly the possibility for an “activity of thought”. Can design be imagined as one possible configuration of this “activity of thought”? And if so, how can we translate this approach into renewed and better forms of design education?

Can we imagine a pedagogy that does not orient students towards progress but rather support them in how to deal with the failures of progress? Looking at Benjamin’s idea of the storyteller (which was also discussed in the previous series of DESIS Philosophy Talks called ‘Storytelling and Design for Social Innovation’), we ask ourselves if design schools can ‘learn’ their students to listen and find these potentialities in the hidden stories of what remains?2

Footnotes

1 V. Tassinari, The Wunderkammer of the Future. Philosophical Notes on on the idea of history in speculative design practices

2 W. Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History“, Illuminations, New York: Schocken Books, 1969, p. 249

3 “Our inheritance was left to us by no testament”, in R. Char, Feuillets d’Hypnos en 1946 quoted in H. Arendt, The Gap between Past and Future, The Viking Press, 1961

4 W. Benjamin, “The Storyteller: Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov“, Illuminations. NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1968

5 W. Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, Illuminations, New York: Schocken Books, 1969

6 W. Benjamin, Illuminations. Shocken Books, New York, 1968

7 W. Benjamin, Illuminations. Shocken Books, New York, 1968

8 H. Arendt, The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 1958

9 V. Tassinari, The Wunderkammer of the Future. Philosophical Notes on on the idea of history in speculative design practices