Adam Gibbons. Blocking

Adam Gibbons writes about the time of the archive, competence, and how the one-off rehearsal was staged in the recent exhibition White Horse/Twin Horse by artist duo Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen.

In the exhibition White Horse/Twin Horse by Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen at the theatre space De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam, in the winter of 2017–18, time is marked. By the months during which the exhibition is open, by the fortnightly periods for which each presentation is on display, by the days between each iteration of these rehearsals and by the hours and minutes of the various animations of the space which are imported by the five collaborators whom the artists have invited to meddle.

The exhibition White Horse/Twin Horse takes place in parts. In many parts. In components; in mnemonic devices, in writing, in enactments, in time.

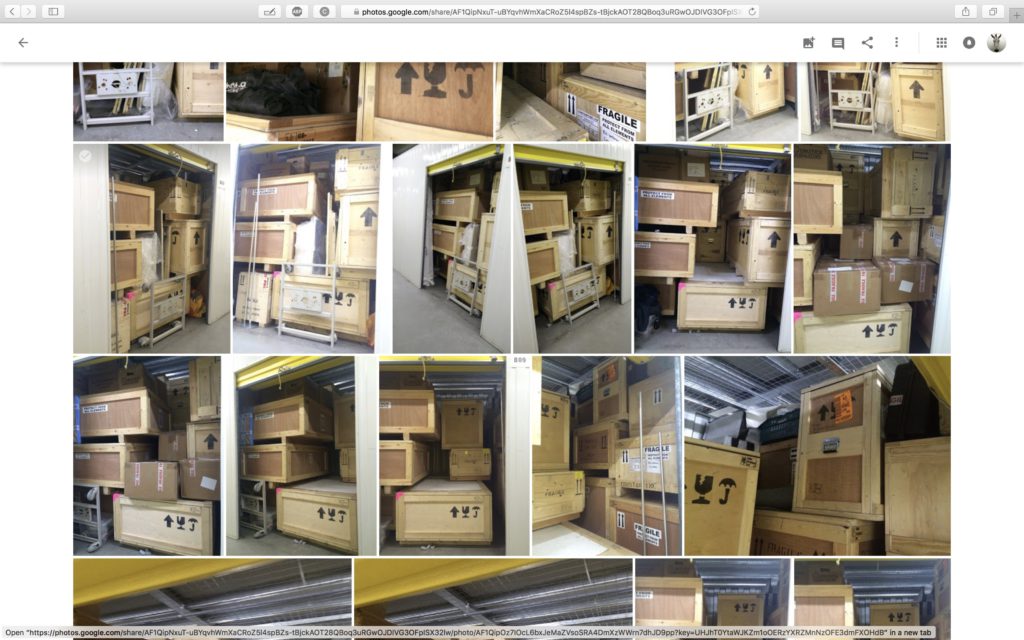

The exhibition White Horse/Twin Horse is dragged out of storage to occupy time. In storage, time is congealed. Time is suspended. Time is ostracised. Objects lie dormant.

In the warehouses of Big Yellow storage, maybe this still time has a colour!

In the public spaces of the theatre, the museum, or the gallery, the pressures of time are once again observable; the wear and tear is on view.

The exhibition, which is divided into five iterations — or rehearsals as the artists would have it — over its ten-week duration, is peppered with fragments of imported language: an archive of subtly shifting artist biographies, a script performed by an actress accompanied by a horse, a forensic ‘crime scene’ presentation, voice recordings of the artists disclosing their methods and anxieties, a transcript from couple’s therapy sessions attended by the artists, and itinerant reviews for each rehearsal.

The exhibition revolves around a notion of full disclosure. Purportedly, everything that Cohen and Van Balen have ever produced as a duo is assembled in this space.

However, when scrutinised, the dichotomous arrangement of a backstage/onstage presence, around which this series of outsourced presentations is premised, gives ground to something far more intimate. Along with the archive of what could be called resolved objects — the duo’s output which is more commonly put up for exhibition — other elements simmer to the surface, are exposed, and exposed to time again: voices that sit between the research going into the production of the artists’ work, or the prototypes they produce.

As is typical for the artists, the title of the show is a kind of readymade remnant, in the form of an anecdote lodged in a project from 2013: 75 Watt, in which the artists produced an object to be made in a factory in Zhongshan, China, whose only function was to ‘choreograph a dance performed by the labourers who assembled it’. Portrayed as a kind of Sisyphean-jive music video, the resulting movements — choreographed by Alexander Whitley — satirise and lay bare the repetitive manual labour performed daily in factories across China at the behest of a Western commissioner. The factory was originally called White Horse. When it began fabricating for the international market, its CEOs discovered another company already using this name and consequently rebranded as Twin Horse. Reluctant to entirely shed their previous identity, the factory would intermittently revert to their former moniker, like a repressed infant identity lingering on. So, antithetically to the mores of marketing, as Cohen and Van Balen say: ‘the factory operates under both names, like a Deleuzian, schizophrenic brand identity’.

The branding move echoes the theatrical binaries of onstage/off stage, character name/actor name. The resulting confusion is mobilised here to draw attention to the instability of a practice which might, in other circumstances, appear to arrive at locatable coordinates at the conclusion of each project.

There are two converging strategies at play in White Horse/Twin Horse: the first, the full disclosure of the unedited archive, the second, an iterative and disjointed series of presentations, authored by invited guests. One can be associated with the agony aunt column or the guilty teenager, the de-clutterer or the first therapy session; the other, framed as it is in the language of drama — rehearsal —, with the theatre.

De Brakke Grond is not a museum, but the strategies are borrowed from the museum’s discourses. It does not have a collection, but a collection (in the form of the self-assembled archive) has been brought into the building. The exhibition could be read as ‘exhibition-as-work’ rather than work on display in an exhibition. Work here would have a two-fold sense: that of the work made by the artists — artwork — and that of the labour of those contributing to the exhibition. An aesthetics of work. People are hired. Crates are displayed (a nod to Marcel Broodthaers’ Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, Section XIXème siècle from 1968?). Labour — cultural, intellectual, technical — is produced in the process and time is marked again here.

Who or what is being displayed? Are the artists who have an exhibition twisting the context in order to be displayed themselves? Are they placed on display by the people who have been invited to perform the labour of defining the display situation, its materials and interpretive tools? Am I co-opted into this process myself in writing this text (at the invitation of the artists)?

Must the collection — if it can be thought of as such — at De Brakke Grond adhere to the logic of theatrical space? If so, does it becomes performative? The museum appears in theatre drag, the artists perform their museum retrospective and by so doing invert their on-stage and their off-stage identity.

Manual labour and its attendant apparatus was a defining metric of time until we arrived at what is sometimes called the ‘post-industrial condition’, the circumstances of contemporary, and often precarious labour, which contemporary art discourse has, for the last decade at least, been keen to put a spotlight on.

In the recent experience of the cosmopolitan Westerner (a category the artists and audience for this exhibition fall into), the rhythms by which we work and experience leisure have undeniably undergone, and continue to undergo, significant change.

The London situation in which the artists live is one of being at capacity. In the familiar story of gentrification, areas which were local shops and businesses ten years ago morphed into artist studios and workshops five years ago, and have now made way for newly built apartments. Universities and developers collaborate to redefine communities according to profit margins. Big Yellow Storage moves to the other side of the ring road.

Performance and exhaustion race hand in hand. Time dictates at megaphone volume.

Labour and labour conditions, as well as materials (the readymade remnants of industrial or ecological experiments) and a strict sense of consequence, are frequently found at the foundation of works by the artist duo. The complexities of projects such as Cohen and Van Balen’s years-long enquiry Trapped in the Dream of the Other, 2017, centred around coltan mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, are belied in the calm and straightforward arrival of the resulting video work; a hovering Steadicam shot that peruses this man-made territory of excavation and the surrounding landscape of the war-torn country. For the video’s duration, remotely controlled fireworks pop in the air around the cameraman (Van Balen) and mine workers, an old Nintendo shoot ‘em up gun (operated by Cohen) triggers the pyrotechnics via a real-time video relay to London. States of leisure, the interfaces which produce these states, and the sites of exploitation (in both geological and capitalistic senses) converge in an uncomfortably un-disturbing composition. Broodthaers might (again) say it’s a question of war and comfort.

From the intense flow and perpetual shifts in a scene of White Horse/Twin Horse, the accelerated production, the expanded network, rapid turnover; the conversations around visibility, iterations, production, flows of labour and capital, you could be forgiven for anticipating a dazzling resolution, a grand finale. In its place, through the archive of work and its positioning by the five ‘curators’ as well as the stunted stubbornness of the single-revolution loop, the one-time-only rehearsals refuse this logic of getting somewhere.

Cohen and Van Balen test. In the studio, on-site, across Photoshop documents, SketchUp renders, with materials. A process very similar to a received understanding of what a rehearsal is (the German word for rehearsal is Probe). A painstaking and thorough process of iterative research and experimentation drives a project to a defining performance.

Perhaps getting somewhere is not the motivation. Perhaps the kind of fierce refusal to move on — as Kathrin Busch observes of René Pollesch’s film Portrait aus Desinteresse (Portrait for the lack of anything better to do) in her text Rehearsing Failure [1] in which rehearsal is straight repetition — is a more appropriate force. A Modernist-critical move in which the drive to self-improvement is substituted for a Bartleby-like uselessness, a hiatus or denial. This too is an attempt at exhaustion.

What is the result of the production of excess cultural capital? (Surely a goal in the networked collaboration/invitation structure here, and more broadly as a thread through the post-industrial condition). Post-labour does not mean the end of labour, rather a reconfiguration of the means and technologies by which labour is exercised, with new targets in the production of surplus. Without giving the work time to settle, how can it acquire the reverent-time required to generate the aura of Art on display? Without rehearsals which hone the performance, how can these objects or displays prove or improve their competence?

Subjected to these conditions, can we witness the archive experiencing an alienation from its own incapacity? Stripped of their auratic-time must these objects learn to behave other to how they have been taught? Have they been exhausted by their outing in the theatre, at the hands of multiple directors? What colour of time will they take on when they go back into storage?

Contributors to White Horse/Twin Horse include:

Anne Breuer

Tyler Coburn

Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen

Christina Li

Samuel Saelemakers

Judith Vrancken

Footnotes

1 In: Putting Rehearsals to the Test: Practices of Rehearsal in Fine Arts, Film, Theatre, Theory and Politics (ed. Buchman, Sabeth, Lafer, Ilse, Ruhm, Constanze), Berlin: Sternberg Press 2017. In her text, Rehearsing Failure, Kathrin Busch refers to Pollesch’s film to introduce an idea of the rehearsal as ‘pure duplication, without added value or transcendence’, p. 133.